by Michael Joshua Rowin

Rocket Science

Dir. Jeffrey Blitz, Picturehouse, U.S.

The major problem with films built from universally experienced subject matter is that they allow little room for suspension of disbelief. We can give a pass to Sunshine, a film about a crew of astronauts on a mission to reignite the sun with a nuclear weapon, for its wildly fantastic implausibility because, heck, what do we know about astrophysics? But set a film in our psychic backyards and the critical antennae go way up. When a film to fails at accurately representing something inextricable from our intimate knowledge of the world it’s not just disappointing, but often insulting.

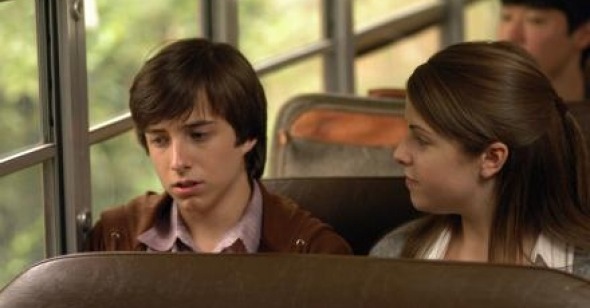

For better or worse, most of us acquired a formative intimacy with the battlefield that is public high school. In Rocket Science, the debut fiction film from Spellbound writer-director Jeffrey Blitz, we are given a tour of that familiar microcosm (as localized in Plainsboro, New Jersey) through the trials and tribulations of Hal Hefner (Reece Daniel Thomspson), a stuttering loser who gets a chance to be somebody when the school and state’s top debater, Ginny Ryerson (Anna Kendrick), improbably grooms him to be her next partner. Due to fine performances by Thompson and Vincent Piazza as older brother Earl, Rocket Science nails a number of details crucial in portraying the comic absurdity of awkward adolescence. Blitz takes great care to avoid obvious generic clichés—if you’re expecting a triumphant showdown, you’ll be sorely disappointed—but this only pushes the film into other, newly minted traps.

Rocket Science places too much faith in the Welcome to the Dollhouse and Rushmore playbooks, wherein humiliations, caricatures, and indie rock songs pile up like so many checklisted punchlines in a strained effort to create a sideshow attraction around a protagonist wrongly labeled a freak. For instance, the film’s wry, Baldwinesque narration (“It was Thursday. It could have been any other day of the week, but it wasn’t. It was Thursday.”) sounds annoyingly incongruous when describing Hal’s earnest humility. Too many little items, like Hal’s best friend’s dad audibly screwing recently divorced Mrs. Hefner, come across as needlessly cheap. Worst of all, the film’s charismatic focal point, Ginny, has absolutely zero correlation to reality. Really, are there any pubescent young women so articulate as to speak and carry themselves like Carrie Bradshaw/Gilmore Girl hybrids? For a film to claim emotional honesty about the lives of outcast teenagers and then try to sell such a false character is more a betrayal than the one Ginny eventually dishes out to Hal.

A friend recently tried to dissuade me from overestimating the recent cottage industry of quirky, offbeat films focused on the maladjusted and weird. But it’s films like Rocket Science—not nearly as atrocious as Eagle vs. Shark but in a way more frustrating—that keep convincing me this is a not insignificant trend. Are filmmakers now so insecure about the meaningfulness of their films that they must consistently undermine any truthful melancholy about high school life with evasive adorability and easy irony? There’s always The Squid and the Whale—another film about teenage casualties of divorce—to inspire confidence that somebody out there can fully capture adolescence in all its pathos and humor, but that film’s release is starting to feel too far off in the past to provide much comfort.