Into the Mystic:

Report from the 17th Views from the Avant-Garde at the New York Film Festival

By Genevieve Yue

The Views from the Avant-Garde program, once a weekend sidebar to the New York Film Festival, has grown into a full-fledged festival in its own right, this year showing the work of 117 filmmakers and artists over a four-day stretch. While undeniably making it richer and more expansive than any previous edition of Views, this abundance of work means also that it is now impossible to see everything. This year saw fewer repeat screenings and more sold-out shows; while that is a testament to the enduring vitality of experimental film, particularly in North America, it also made it difficult to see more than a small portion of Mark McElhatten’s meticulously assembled program. McElhatten himself was unfortunately unable to introduce the screenings, though a number of curators, festival directors, and other members of the avant-garde community (myself included) stepped in to present his selections. As much as the Views slate reflects McElhatten’s vision in showing frequently surprising and always challenging work, it was, and has always been, also about a community that comes together to watch films, to discuss and dispute them, and to renew itself in the process.

Part of the festival’s pleasure comes from the discovery of older work. Manuel De Landa’s Magic Mushroom Mountain Movie (1973–80), presented by Anthology Film Archives, was shown in a digital transfer from its original Super-8 format. For years, the ethnographic film languished, as Landa had forgotten about it, in part because he had been high on mushrooms during its shooting over the course of several years in the Oaxaca region of Mexico. The filmmaker’s blithe abandon is apparent in the footage he captured of rambunctious children, an old woman eating a piece of fruit, a street procession dotted with umbrellas, and a girl aiming a camera back at De Landa. The film is loosely strung together: occasionally a frame of text marking the year interrupts the shot, but the dates don’t seem to matter, as there’s no discernible break in time. Rather, we’re presented with the same exact scenes, only momentarily punctuated by title cards. In this delirious, joyful world, the distinctions in these time markers are arbitrary, even laughable, compared to De Landa’s timeless adventure of seeing. Another Anthology presentation was Stom Sogo’s Around the World (aka Speedy Speedy California Sky), a diaristic amalgam of footage culled from previous works, many of them shot in the mid to late nineties, and here edited on an undated video found on a hard drive, after Sogo’s death in 2012. The superimposed views of trees, puddles, and telephone wires—which, because they appear so briefly, are more like suggestions of shots—are like the images we see as we’re falling asleep. A gleaming surface of a car, the side of a child’s face, or a group of people crossing the street appear somewhere on the precipice between impressionistic sketch and dream, awash in color, and scored to the sound of static, or, in other parts, choreographed to an electronic beat.

Views also nurtures emerging talent, and after her debut last year with the ritualistic short Tokens and Penalties (which I mentioned in my 2012 round-up), Talena Sanders returned with an accomplished experimental feature, Liahona, as well as an installation, The Relief Mine Company, which showed in the Elinor Bunin Munroe Amphitheater. Liahona, which refers to a mystical compass that helped the first Mormons find their way on their difficult journey to Utah, examines the culture of the church in its shrouded mysteries, its contemporary banalities, and its myriad contradictions. Sanders includes shots of the tours of Salt Lake City’s Temple Square welcoming visitors in a number of languages, the solemn procession of actors in the Mormon Miracle Pageant, and families waiting in the airport, ready to greet their sons returning from faraway missions. The film paints a picture of a religion deeply invested in international expansion, though, as Sanders noted in her introduction, the church is currently experiencing its steepest decline since its founding. Voices fill her images, from harrowing accounts of suffering and miracles of faith along the thousand-mile Mormon Trail in the 1840s, to recent church elders preaching a cheery, wholesome message to an increasingly diverse constituency. Late in the film, Sanders adds to these accounts a series of stark facts, rendered in silent white titles against black frames, that depict a significantly different Utah, one with high rates of pharmaceutical drug abuse and suicide. For her part, Sanders locates herself as an ambivalent former member, at first only a name hesitatingly pronounced when a church volunteer leaves a voice message inquiring about her standing in the church. Later Sanders provides details of her upbringing as a Mormon, and her own quiet rebellion, revealed in a conversation with her former fiancé, when she left the church and became an artist. Through art, of course, she eventually returns. The wide-ranging Liahona is neither a straightforward indictment nor a reconciled embrace, but a story inextricable from its artist’s own.

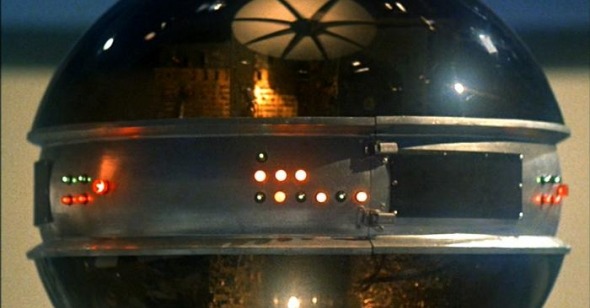

Jesse McLean’s The Invisible World also offers a defamiliarizing view, taking as its subject our cluttered consumer culture. She examines the bubblegum colors of cleaning products and, posed against a salmon pink backdrop, a series of disparate objects seemingly culled from a thrift store: a red leather ottoman, a small porcelain shoe, a Scrabble board game, and a number of outmoded cameras. Aside from the disembodied voice of an elderly woman emanating from a blinking electronic orb, and the legs of a woman modeling footwear, people are largely absent from McLean’s film, or what a subtitle describes as “a parallel universe of matter, indifferent to human experience.” Here, objects, whether isolated or accumulated, have a kind of totemic, even magical presence. They overwhelm human existence—in one shot, a hoarder’s stacks of books suggests that they construct a walled prison—but also survive it, creating a strange life of their own.

With Movement in Squares, one of three films he presented at Views, Jean-Paul Kelly similarly examines the material remains of people long since gone. In a split-screen view, one frame shows YouTube footage of realtors documenting the interiors of foreclosed homes, while the other is a close-up view of the artist paging through a book of the painter Bridget Riley. Riley’s voice, heard commenting on the nature of optical illusion, is added to the sounds of the realtors stepping from room to room, and the combination produces an uneasy connection between the stark evidence of abandoned homes we see and the reliability of our own perception. In one instance, when Riley notes the type of images that confuse the eye, we see a flashlight moving frantically on a wall, the cameraman perhaps agitated by the sight of forcibly vacated homes. The suggestion of violent removal, in addition to the disarray of overturned furniture we see throughout, is most troublingly expressed in a shot of a handprint on a window, dead flies stuck in its sticky smear (the shot recalls insect bodies scattered atop a skylight in The Invisible World). This image intimates trauma: a desire to escape, perhaps, and the inability to do so. The Riley text, however, destabilizes what we see, reminding us of the illusory nature of all images. In Kelly’s Figure-Ground, for example, colored squares placed in the center of the frame block out the line-drawn renditions of several crime scenes which are otherwise indicated in brief glimpses of photographic evidence: Trayvon Martin’s cell phone lying in the grass, a pair of slippers belonging to Bernie Madoff after the state auction of his assets, the neck tattoos of Benjamin Colton Barnes, an Iraq veteran who murdered a park ranger on New Year’s Day in 2012. What appears most steadily throughout the film, however, are the colored squares, which seem to tremble with the high pitched hum on the soundtrack. These blocked out shapes are vanishing points according to classical Renaissance perspective, dots that suggest infinite depth, but also vanished ones, that severely delimit our sight, abstract markers for lives that can never be fully recovered.

In a different register, Rebecca Meyers works with fleeting imagery in murmurations, a film acutely attentive to the flash of a bird’s wing, the swift turn of an avian head, and the subtle shifts in light over the course of a New England summer, autumn, and winter. Meyers films a blue jay landing on a branch, a flock of Chimney Swifts passing across a clear sky, and a magisterial great blue heron perched in the middle of a tree in the Mt. Auburn cemetery in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Many of these shots last just as long as the birds hold still. The delicacy of these scenes is occasionally interrupted by the sharp sound of a woodpecker, another bird’s honking mating call, and, in acoustic close-up, the deep rumble of a cat’s purr, though the film’s sense of observational calm is hardly disturbed. While Meyers was editing the film, she broke her ankle, and, in view of her injury, murmurations is suffused with a lightness, even possibly a fragility. Undeniably, however, the film conveys an altered mobility, a feeling of moving through life at an altered pace, and a view of the world perceived with the sensitivity of its fleetest creatures. Saul Levine’s Falling Notes Unleaving similarly looks to nature to articulate personal experience, in this case the gathering of friends for the funeral of the filmmaker Anne Charlotte Robertson in Framingham, Massachusetts, as well as the mountain forests outside of Portland, Oregon. Here, again, a sense of delicacy, as Levine’s 8mm camera is shaken by the same wind that rustles the trees in both locales. But there is also the vibrancy of the autumn foliage, with broad red, green, and yellow leaves bowing on low branches, and brilliant, blurry circles that dance across the screen. Levine films people in synch with this natural splendor, following them as they venture to a secluded waterfall or rest on a stout log, as one woman does while nursing her baby. Before his screening, Levine offered Falling Note Unleaving as both an elegy for people that have passed, as well as a kind of passing practice of analog filmmaking, but in the dilated view, experimental cinema, which at Views encompassed a range of digital technologies as well, is alive and well.

This continued vitality of experimental film could be found in numerous selections, including, I am certain, more films than I had opportunity to see. Those presented by Mike Stoltz were but two examples of this: In With Pluses and Minuses, a grate of small circles, each a small aperture to the landscape beyond, spins rapidly in front of the camera, building to a dizzying, rhythmic dance. With this seemingly simple device, a surface that both reveals and conceals what lies beyond it, Stoltz manages to convey an acute dynamism reminiscent of the kinetic animations of Len Lye. The camera in Ten Notes on a Summer Day, meanwhile, fixes on a young woman standing against a painted blue wall, the sun partially lighting her face, the sound of distant traffic in the background. Offscreen, a guitarist plucks single notes, and the woman hums along. When the music falls outside of her vocal range, she switches to a lower octave, her mouth turned up in a small grin. Later, she frowns slightly, seemingly unable to find her note. Gradually her confidence builds and her smile returns, though her humming is no longer anywhere close to the guitar’s pitch. Ten Notes is a marvel; it’s as unhurried and refreshing as this woman’s singing, which, though off-key, produces an unexpected harmony, a little song discovered in the process of its own making.