Rock ‘n’ Roll Middle School

Jeff Reichert on School of Rock

For a few brief minutes I actually liked Cameron Crowe’s bio-rock opus Almost Famous. Snuck into the middle of an otherwise unremarkable soundtrack for an unremarkable rock film was Carl Wilson’s finest hour, the utterly transporting “Feel Flows,” from the Beach Boys’ 1971 oddity Surf’s Up, which I’d heard, but never experienced in quite that way. Four years later, I honestly only half-remember the scene it played over, though each of the many listens I gave it following that screening are inextricably linked to this idea of it being “the only good thing about Almost Famous.” I often wonder what would have happened had the song taken audiences out of the movie in the same way I was. Would Cameron Crowe have still won an Oscar? Would we still be deluged with Kate Hudson romantic comedy vehicles? Would Elton John’s “Tiny Dancer” have been re-introduced into the pop music lexicon? I’m sure many readers can recall a similar experience, sitting stunned by a song-image combination, whether it be unfamiliar, enticing music, or a track held near and dear wholly recontextualized. Either way: therein lies the essence of pop. “Feel Flows” is the kind of song that leads obsessive record collectors to march on past Pet Sounds and Exile on Main St. in the hopes of finding the chorus, lyric, or riff that re-captures some piece of past glory. For me, the insertion of “Feel Flows” into Almost Famous activates everything that’s exciting about rock and rock history—the way it’s constantly being written and re-written, the connections, the movements, the possibility of transport and most especially the active work of the music lover towards discoveries that could effect a sea change in their own personal road map through rock lore. These are all things I personally love about rock. But what I perhaps admire most is how little one needs to share in that kind of obsession to be wholly moved by it.

Of course, the brief pop bliss of “Feel Flows” is only a scant five minutes relief in the course of a film more intent on entombing and encapsulating rock into an utterly definable history even as it purports to exalt its legacy. I harbor a sneaking suspicion that the critical accolades strewn about Almost Famous are more the product of writers who lived a much less adventurous Seventies than Cameron Crowe, (but who amassed comparably impressive record collections) admiring a version of the lives they would have killed for. To this considerably younger rock fan, Almost Famous’ R-rating, for “brief nudity and drug content” belies an airbrushed and sanitized PG-13 core that fits it subject like a four-fingered glove. It’s a hugely selfish work—“I was there and you weren’t” it seems to be saying at every turn—but even more so, a saddening one coming from a filmmaker who just 11 years earlier turned a shitty boom box blasting Peter Gabriel’s “In Your Eyes” into one of the most generous, iconic cinematic moments of the Eighties. In late 1999, with only “Feel Flows” weighing its favor, imaging Almost Famous as an auger of the 21st century rock film was a pretty bleak proposition. Thank fucking God, then, for Richard Linklater’s School of Rock.

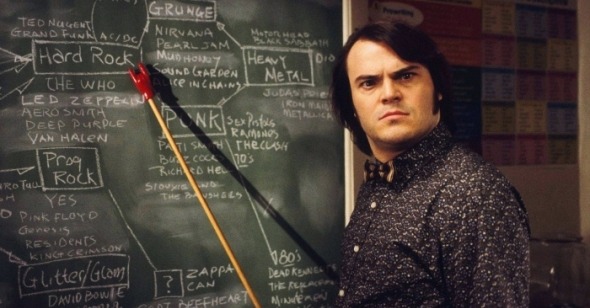

That Linklater’s PG-13 eighth feature can do more for rock ‘n’ roll with a bunch of fifth-graders acting out a shopworn self-actualization-through-group-coordinated-by-lovable-misfit narrative than Crowe can manage with a flash of Kate Hudson’s breasts and sackfuls of stage cocaine is testament to Linklater and screenwriter Mike White’s true reverence for their subject. The expansive implications afforded the word “rock” here is rivaled in recent cinema only by the constant growl of “pirate” in Pirates of the Caribbean. In both cases, the words balloon far beyond their respective “meanings” to encapsulate a sense of secret histories, alternative ways of being. Think of School of Rock as a film that performs the same operation—I don’t need to tell you what it’s about, or what happens as it’s (mostly) obvious. But knowing beforehand in no way ruins the fun. Unluckily released during the first week in Billboard history which found all of the top singles charts slots occupied by the latest in hip-hop, School of Rock found this moment wielded, by the Armond Whites of the world, as a weapon against a legitimacy it never claims. I suppose re-casting the film as School of Hop, and transforming a class of students into some version of the Roots rather than prepubescent punks might have made School of Rock more of this moment, but when was the last time we’ve seen a studio film that’s so resolutely, stubbornly unfashionable? Those who did like School of Rock tended to love it, but only for its looks. Sure, it’s great fun paired with massive cock-rock riffs, and it handily outsmarts the majority of multiplex dreck, but there’s a real intellectual agenda at work in School of Rock that’s completely complementary to the rest of Linklater’s films. It’s smarter than Jack Black looks. His character’s massive, Levitican flow chart of rock should have been the first clue. A second look at any of Linklater’s other works would have made this somewhat obscure object unmistakable. School of Rock is far more than the sum of its more traditional components, and, though it might sound ridiculous, I’ve often wondered if it might not be the most perfect distillation of Linklater’s ideas yet.

Though I’ve never been much of a fan of Jack Black’s antics (if Adam Sandler’s less accessible, rampaging id were given physical form, I imagine it’d look and sound something like Black), I’ll be the first to argue that his constructed star persona goes a long way towards elevating School of Rock. However, this bravura performance is only truly possible given the oh-so-tenuous scaffolding White and Linklater erect around him—a delicate structure that carefully balances Dewey Finn, mediocre-burnout-guitarist, Dewey Finn, greatest-rock-sponge-of-all-time, and “Ned Schneebly,” fake-middle-school-substitute-teacher-extraordinaire, with of course, Jack Black. When Dewey first, uncomfortably, offers to perform his epic work-in-progress (call it “The Band is Mine”) for his class, you can almost sense the various personalities behind the film working together like some invisible machine. Black (expectedly) rips a page from his Tenacious D songbook, but what’s unexpected (if you’re not thinking Linklater) is how the camera drifts ever so slowly, and lazily backwards, capturing the whole performance in a single maneuver. Instead of taking the easy road to reaction shots, the camera’s gaze is perhaps more than a little puzzled, but ultimately completely endeared of its subject, ridiculous as his compendium of rock star moves and clichés may render him. It’s the most amazing, yet wholly incongruous, thing one could imagine occurring within the aforementioned shopworn narrative—so strangely cubist that it stops the film completely in its tracks. Try to imagine a comparable moment in Sister Act. If School of Rock hasn’t won you over by this moment, you’re in the wrong movie.

Conceiving of individuals as containers for diametrically opposed forces is a hallmark of Linklater’s work. After all, in the course of his filmography he’s offered Dazed and Confused’s rootless/rooted David Wooderson (Matthew McConaughey), Before Sunrise’s cocksure/unsure Jessie (Ethan Hawke), Tape’s wounded/wounding Vince (Hawke, again), and plumbed the ultimate contradictions of the un/conscious mind with Wiley Wiggins in Waking Life. It’s this conscientious eye that keeps School of Rock from collapsing into self-parody, or worse, schmaltzy pap. In Linklater, nothing is ever as simple as it seems, but then nothing is ever quite as complicated as one might like to make it. With a body of work so intent on gently exploring the myriad potentialities of the individual, it’s easy to understand how Linklater’s biographical data (college baseball scholarship to oil worker to filmmaker) influences the whole of his filmmaking. For him, everyone has something interesting to offer, some possibility of expanding beyond simple labels. Though the script is White’s, Linklater’s attraction to the project is obvious—Dewey and his students are like any of his other protagonists. They just rock harder.

This overall generosity towards the individual opens Linklater’s films up to group interactions and movements between characters that are harmonic, if not borderline symphonic. And, as one might expect, Linklater’s vision of rock is a distinctly participatory one—just because you’re not “in the band” doesn’t mean you’re not “in the band” Dewey offers to those students who aren’t actually chosen to play instruments. If the full profundity of the statement may be lost on him, it’s certainly not lost on White or Linklater—the students (nearly all of whom take on lives of their own) are assigned to positions across the rock spectrum: guitar, bass, drums, security, lights, style, groupies. Tellingly, no position is too great or too small. He may spend extra screen time teaching his lead guitarist to windmill properly, or his bassist to assume the proper facial affect, but one always feels the weight of those equally important moments we might not be seeing—vetting lighting schemes, security plans, or working out transpo with the band manager. In true egalitarian spirit, all the major players in School of Rock are afforded a chance to let their hidden rocker out—even Joan Cusack’s tightly wound school principal collapses into Stevie Nicks halfway through a beer. Aside from the aggressively static character played by Sarah Silverman (predictably ejected by film’s end) the film’s transformations are all finely telegraphed in miniature, each given just enough screen time to outline its full arc before moving on, a series of small gestures that add up to a surprisingly believable whole that culminates in (what else?) glorious rock catharsis.

Still skeptical? If you haven’t seen School of Rock, it’s easy to be. Linklater’s filmography is full of films that sound like obvious missteps on paper but end up bursting off of the screen. One night Franco-American twentysomething love affair? Blecch. Genial western? Ha. One-room, three character DV-cheapie? No way. Jack Black children’s movie? Rrrright. Yet each time we’re left to recognize that at the heart of each of these disparate works is unmistakably nothing less than Richard Linklater. Remove the guitars, drums, and, well, rock from School of Rock, and you’re still left with that kind of velvet revolutionary leading the uninitiated to which his cinema is partial. Often ineffectual, perhaps, but try as you will and you’d be hard-pressed to find a heart in the wrong place in the whole of his oeuvre. Naysayers could argue School of Rock as the flippant cousin to treacle-fests like Dead Poets Society and Mona Lisa Smile, but consider it coming from the probing, thoughtful consciousness behind Waking Life and it meshes, like all of his other films, perfectly into the overall body of his work

Having never got the Led fully out in high school, I may not be the most qualified to judge School of Rock, but I find it without peer thus far in the first decade of the 21st century. Though it hearkens back to kind of rock far from the current vogue that celebrates the rock musician as vegan-introspective-activist-poet, it suggests something in the music that carries over regardless of genre. “Sticking it to the man” may be the film’s oft-repeated raison d’être, but speaking softly in the background is a narrative about collaboration and teamwork, participation, discovery, and of course, playing one great show. The history of great rock is nothing more than a history of great, often fleeting collaborative moments (formed most often at the point of interaction between performer and listener), and that’s what’s really being learned in School of Rock—the immense value in those instances of coordinated impact. How else could Dewey begin educating his students (after being fed) than tearing up his predecessor’s record of the student’s individual achievements? Of course everyone gets their chance to solo, but there’s no better filmmaker working than Richard Linklater to show audiences how the most triumphant moments are often those of stepping back from the spotlight and into the fold.