New York’s Alright If You Like Saxophones

Nick Pinkerton on Permanent Vacation

I went to see Jim Jarmusch speak a few years ago, and he seemed like an effortlessly laid-back guy—cool, for lack of a better word. He was presiding over a retrospective of his filmography at the Wexner Center in our mutual home state of Ohio, sharing the stage with Chicago Reader critic Jonathan Rosenbaum, author of a slim BFI Modern Classics volume on Jarmsuch’s movie Dead Man. The two managed a pretty good Mutt and Jeff routine between them: squat, professorially maned Rosenbaum prodded and praised excitably while the lean, unflappable director shrugged off analysis and goofed for the crowd. Jarmusch had a hipster’s ease about him—I don’t mean this in the pejorative, authenticity witch-hunt sense that’s become so popular lately, just in a kind of relaxed old-school hepcat way. Maybe he was just jet-lagged and a little drunk.

Whatever the case, I’ll always remember him as a prototypical cool guy, a semi-stoned musician kind of cool guy—he’s even said that it was lack of musical ability that by default led him to filmmaking. If I felt like playing “spot the influence” with his body of work, I think the list would end up heavily favoring bands. I think that some lofty, jazzy idea of cool is pretty vital to Jarmusch’s essential works—it’s hard for me to separate his movies from the context of some far-out Downtown spiritual heritage leading from Ginsberg through No Wave—and his films feel as much like “Beat filmmaking” as Pull My Daisy (which Jarmusch screened at that same retrospective). He shares with the Beats that same restless exuberance for travel, for foreign places and sounds, spurred by a played-up sense of cultural homelessness; that same sentimental penchant for self-poeticizing pockets of romantic aloneness in the night; that same obsession with fluid, loose-limbed going-with-the-flow. But there’s something in Jarmusch’s flicks that’s okay with me while Kerouac’s insistent ecstasies just irk; maybe it’s the filmmaker’s deadpan drollness and those little moments when he reveals fissures of lack behind the bluff. Like the “bored because they’re boring” travelogue of Stranger than Paradise. Like Yokohama hepcat Masatoshi Nagase in Mystery Train, whose much-voiced preference for Carl Perkins over Elvis Presley belies a serious cool complex, and who we see trying to shrug off sexual ineptitude with a surly front. Like feckless little dork Roberto Benigni enjoying Down by Law’s only happy ending (and woman), while Tom Waits and John Lurie are left to out-slick each other with too-slow handshake disses.

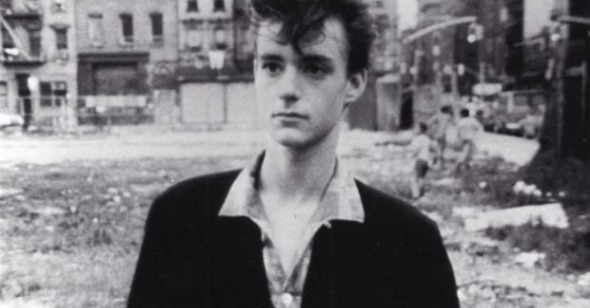

Jarmusch’s little-screened collegiate 77-minute debut feature, Permanent Vacation, is another movie wrapped up in cool, but the humor and circumspection marking those later films is absent. For a protagonist we have Aloysious Parker (Chris Parker), a skinny, swan-necked, out-there kid who dresses like a Fifties jazz sideman and sports a greasy Charlie Feathers ’do. Don’t expend too much energy wondering how this honky wound up with a brother’s name—it’s as natural and Downtown as Lou Reed singing “I Wanna Be Black” or James Chance’s whole “white soul brother” routine. Allie hangs around his cold water flat, musing in voice-over on his complete sense of disconnect. He dances alone while his dour girlfriend smokes the day away, shimmying himself into a fever to the tune of an old 45; he reads a passage of Maldorer out loud, finally dropping off, concluding “I’m tired of this book”; he leaves their bedroom with the mattress on the bare floor (it reminds me of a postcard I used to have of Richard Hell in his apartment) to wander littered alleyways, floating on the vertiginous sax bleat of Jarmusch and John Lurie’s soundtrack. After dropping by to see his mother in the asylum, Allie visits the now-defunct St. Marks Cinema where Nicholas Ray’s The Savage Innocents is screening (the poster in the lobby is on loan from Ray’s widow, Susan), where a gorgeous and unhappy art-school cutie with a sensuous frown half-remembers the movie to him. Finally, he steals a car (a black chick on the street enthuses: “That dude was wild style!”) and uses the proceeds of his theft to hop a boat for Paris—we last see him staring scrunch-faced and blasé off the deck, sporting a shameless white cravat and speaking the title line in a cringingly on-the-nose voice-over thesis statement. Aloysious is one of those incurable wanderers, and the call to move on has come: “That’s it—time to split, time to go someplace else.”

This movie, where it’s been written on, has benefited hugely from knowledge of Jarmusch’s high-profile future; it’s draggy and at times intolerably Amos Poe–faced. Where this aloof, zilch-budgeted project does work—for me at least, though this probably says more about my own romantic hang-ups than anything else—is in encapsulating what it could’ve felt like to skulk through a certain time and scene in New York City. The film takes place in a near-deserted wreck of a metropolis, in the aftermath of some vaguely alluded to half-apocalypse (a war with the Chinese, it seems), and the now-legendary squalor of Big Apple on the brink of the Eighties seems appropriately crumbled by “landlord lightning.” Watching Parker vogue past Dresden-like vistas in his thrift-store sports coat, I had to think of the NYC of the compulsively readable, if dubiously reliable, punk history Please Kill Me, an ailing city that abandoned its downtown no man’s land to decay and gutsy, pretentious kids. I love that cooler-than-thou Manhattan for those moments when its accomplishments matched the heights of its dandyish self-regard; it’s easy enough to take potshots at some pompous, ectomorphic square from Delaware who moves to NYC and starts a band and lifts his stage name from a 19th-century French symbolist poet—but then just listen to Marquee Moon…

Permanent Vacation is no masterpiece; it’s unpolished, the sound is murky and shittily recorded, but overall Jarmusch’s wispy tonal filmmaking, including a sequence of Ozu-cribbing, empty establishing shots, is far more sophisticated than, say, Ulli Lommel’s Blank Generation from out of the same scene. The movie’s puffed-up melancholia and unabashed love affair with being a hip, unattached, good-looking young guy is winningly straight up. It’s enamored with the simple acts of turning on a record player, going to a repertory house, or walking around the city and seeing some crazy shit—enamored enough to make a movie out of all that stuff. I like Permanent Vacation for that, even if the flick is so startlingly full of itself; it’s a movie by the coolest guy in his NYU class, and it feels like it, sometimes painfully so.

Permanent Vacation lays out the template for future Jarmusch films featuring cool cat wiggers playing incredulous dress-up in the inner city (John Lurie as a New Orleans pimp? Limey Joe Strummer a blue-collar dude in downtown Memphis?); it’s easy to scoff at, for sure, but a lack of irony or condescension in these games of racial appropriation helps put the conceit through. The easy dialogue between white and black hipitude that Jarmusch strikes never feels one bit nasty or hands-off like some snide art school brats with removable gold teeth who rah-rah-ed Ol’ Dirty Bastard’s kooky crack habit. Permanent Vacation and the movies that follow it are unmoored drifter’s stories, and, to borrow from Down by Law, they simply realize that the slums can be pretty “sad and beautiful” when you’re just passing through. Tourist Jarmusch keeps his eyes open in neighborhoods where nobody wants to be and, at his blue-note best, in Permanent Vacation and its kin, finds a little bit of the downbeat poetry of a lyric from David Berman’s Silver Jews: “When the sun sets in the ghetto/ All the broken stuff gets cold.”