A Man and a Woman

By Chris Wisniewski

Orlando

Dir. Sally Potter, UK, Sony Pictures Classics

It isn’t surprising that filmmakers have largely avoided adapting Virginia Woolf’s novels. The ellipses and fragmentary perspectives that characterize masterworks like To the Lighthouse and The Waves might lend them a certain “cinematic” quality—at the level of narrative structure, they are suggestive of montage—but the books resolutely foreground interiority while eliding incident. Her plots are often banal or hopelessly obscure, but the thoughts and feelings of Woolf’s characters, conveyed in stream-of-consciousness prose, reflect and sometimes critique their social, political, cultural, and historical circumstances. Her books are journeys of the mind particularly unsuited to the very literal medium of narrative cinema, which tends to reveal psychology through event (Woolf usually travels in the other direction). Marleen Gorris’s 1997 film version of Mrs. Dalloway, from a script by Eileen Atkins, is a perfect case in point: Vanessa Redgrave conveys warmth and a gentle weariness in the title role, but her knowing smiles and heavy sighs alone can’t make us care about her aging socialite or her over-planned evening party, nor does Gorris manage to bring the book’s disparate threads together into something that feels monumental rather than mundane.

Uncharacteristically for its author, Woolf’s 1928 novel Orlando, inspired by the life of her lover Vita Sackville-West and arguably the only of her books to serve as source material for a successful film, overflows with incident. Orlando charts its titular protagonist over the course of four centuries, from the Elizabethan era to Woolf’s present. It opens with Orlando as a young nobleman and follows him across continents as he embarks on failed careers as a poet and ambassador. Then, Orlando changes sex and returns to England to defend her inheritance and to fall in love. It is anything but mundane.

Sally Potter’s marvelous 1992 film of this undeniably strange, altogether wonderful book now makes its way back to theaters after a digital restoration, and in a bleak cinematic landscape, this oddball film feels especially vital. While it’s decidedly unlike Woolf’s other most widely read novels (e.g., To the Lighthouse, Mrs. Dalloway), Orlando would also seem to be an unlikely candidate for cinematic treatment, though it feels unadaptable for altogether different reasons: a narratively dense, suspension-of-disbelief challenging fantasy, Orlando makes no excuses for its flights of fancy and contains an excess of plot. Retaining its improbable chronology, Potter streamlines, justifies, and explains, organizing the film into a series of episodic vignettes that hit the major milestones of Woolf’s text (“Death,” “Love,” “Poetry,” “Society,” etc.) and providing context for Orlando’s mysterious longevity. (“Do not fade, do not whither, do not grow old” commands Queen Elizabeth I, played here—in an amusing but appropriate gender-bending twist—by Quentin Crisp.)

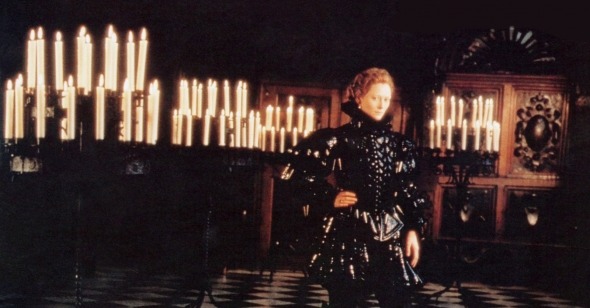

Potter’s screenplay is faithful without being slavish, and as a director, she inventively captures the spirit and tone of the source material in uniquely cinematic ways. There’s a lightness and humor to Orlando—the book and the film—and a formal inventiveness that helps catapult both reader and viewer through history. Where Woolf transitions from the 18th to the 19th century in a dazzling passage in which a “turbulent welter of cloud” covers London at midnight, Potter chases Orlando (Tilda Swinton) through a garden maze in a series of briskly edited handheld and tracking shots. In one cut, Orlando’s costume changes from 18th century to Victorian attire; then Potter cuts to a reverse shot, and back behind Orlando as she dashes into a cloud of fog.

Stylistically, Potter takes chances early: the movie opens with a shot of Orlando pacing at a tree, reading. As the camera pans left, then right, then back, he utters the novel’s first line in voiceover (“He—for there could be no doubt of his sex, though the fashion of the time did something to disguise it . . . ”). Swinton, all ambiguous, wily charm, then turns and stares into the camera, declaring, “That is I.” It’s the first of many times Swinton breaks the fourth wall by staring at the audience. The conceit mirrors Woolf’s tendency to directly address her readers in witty asides, in which her third-person “biographer” acknowledges and exposes the constructedness of her written account of Orlando’s life. Potter, too, is exposing the artifice of her medium, but in doing so, she asserts a first-person, rather than a third-person, perspective. If the book is a communication from biographer to reader, the film eliminates the exegete. Woolf subtitles her novel “a biography,” but Potter’s film could more accurately be called “an autobiography annotated with music” (David Motion and Potter wrote the film’s musical score, and two original songs performed by Jimmy Somerville in a distinctive falsetto bookend the movie).

To sell the conceit that Orlando stands both inside and outside of the story, Potter relies fully on Swinton’s intelligent and wry performance, which helped to turn the future Oscar-winner into an art-house star. Androgynous but beautiful, Swinton’s Orlando doesn’t simply change gender; she grows from naive young man barely equipped to handle grief and heartbreak into a modern woman by the movie’s close. As a performer, Swinton is knowing without being arch or detached. When Orlando turns to first see him/herself as a woman, standing naked in a mirror, (s)he looks in the camera to say, “Same person. No difference at all...just a different sex.” It is the film’s single most pivotal moment, and it relies on an absence of irony: At the level of dramaturgy, it asserts a continuity between the male Orlando and the female Orlando, a continuity essential to the movie’s coherence; politically, meanwhile, it suggests the radical possibility that identity is not fixed or determined by sex.

Of course, Orlando’s contemporaries circa 1750 don’t agree. When she discovers that she may lose her house because she is considered “legally dead,” Orlando’s told that being a woman “amounts to more or less the same thing.” In the eyes of the state, one’s sex may indeed make all the difference, but in losing her legal status, Orlando finally achieves a certain freedom—not necessarily from gender roles but rather from claims on her self. After she refuses a marriage proposal from the Archduke Harry (John Wood) he responds incredulously, “I am England . . . and you are mine.” The male Orlando, too had been told by Queen Elizabeth, “All you call yours is mine already.” Sex—or gender—is only one small part of it: Orlando’s story is less about the journey from male to female than it is about self-discovery, and femininity isn’t the end point—self-possession is.

To call Potter’s Orlando a great feminist film is to say too little and too much at the same time. If “no difference at all” encapsulates its progressive attitude towards sexual identity, the film stakes its most essential claim at the very beginning, with a statement that is existential as much as it is, finally, also feminist: “That is I.”