Crude Awakening

By Leah Churner

Agnes and His Brothers

Dir. Oskar Roehler, Germany, First Run Features

Sometimes I paralyze myself by thinking about the number of earnest-yet-terrible non-Hollywood films Iâve seen. Whopping failures underscore a depressing truth: genuine enthusiasm and artistic self-esteem are rarely adequate cinematic resources. When I consider the majority of notches on my moviegoing bedpost, I realize that most are names Iâve forgotten or would like to forget. Carving out another notch before tossing the film into the slush pile of my memory is lonesome enough, but the task of hacking up disposable invective about yet another casualty of blighted indie ambition feels like kicking a dead dwarf.

Not that Agnes and His Brothers is exceptionally repulsive; few films are. Itâs boring and full of despicable characters, it suffers greatly from plotline packrat syndrome, and is frustratingly bent on lending credence to stereotypes about Germansâ lack of humor and poor taste in pop music, perhaps, but itâs also fairly derivative. I find the most irritating thing about Agnes and His Brothers to be its unofficial tagline, a seeming accolade from Variety: âa Teutonic version of American Beauty!â For one thing, the phrase is a truncated version of an unflattering sentence, with added punctuation. For another, it has the suspicious ring of a marketing pitch reconfigured as a reviewerâs original ad blurb. (Indeed, the producer confirms this in an interview by saying he always envisioned this project as âa kind of ââGerman Beauty.ââ) And apart from all that, after several recent years of wildly popular dysfunctional family dramedies clogging our cathode ray tubes and slipping through our projectors, do we really need another American Beauty? Is every affluent, unhappy population in the West entitled to a national spin-off? Indeed, here come a band of disenchanted Krauts of a distinctly 21st century flavor to hold up a mirror to our fashionable flaws as if to say, âLook how fucked up we are! We deserve a book deal! A memoir! A miniseries!â

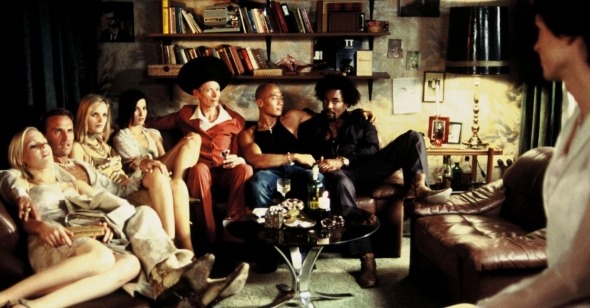

Oscar Roehler has surely cultivated the correct ingredientsâtwo of the leads (Moritz Bleibtreu and Herbert Knaup) are recognizable to American audiences from the wildly popular Run Lola Run, and the other lead, although a novice, is playing a transgendered person. Ka-ching! Also, to convey the mood for his broad-yet-dark comedy, he employs the bargain-bin irony of bright, colorful visuals and quirky music we have come to expect from Desperate Housewives and the rest of primetime American television. If anything, Agnes and His Brothers deserves some distinction for being more outlandish and risquĂ© than Housewives and American Beauty, but itâs also far less graceful. It brushes up against many themes of family and sex but lacks any redemptive dimension, to borrow an apt term. So much is missing, despite Roehlerâs insistence on adding as many twists and turns as possible; he seems to think that if he simply keeps up the narrative momentum, he can at least hypnotize the audience, which is better than actually putting them to sleep.

Agnes is the middle sibling. Young Hans- Jörg (Bleibtreu) is a self-professed sex-addict and ex-bed-wetter. He works in a library stocked with beauties, a maddening Schwarzwald where exposed midriffs and thighs skulk dangerously among the stacks. His inclination toward peeping-tomery gets him banished from the ladiesâ restroom and fired from his job, and it seems that Hans- Jörg will die of shame, when suddenly, he fixes all his problems by appearing in a porn flick and running off with a costar. Sheâs just perfect; a living blow-up doll upon whom he can project all of his fantasies and who guarantees to resolve all his suicidal-mother issues by loving him unconditionally forever and ever.

Werner (Knaup), the eldest, is in his forties. A politician in the public eye with a humiliating home life, he lives in a glass house (literally) and is surprised when heâs caught shitting on the floors of various rooms (itâs gross). He is driven to this odd behavior (along with aggressive yard work and BBQ frankfurter-gorging) by a paranoid suspicion that his icy wife and teenage son are sexually involved. He dreams of murdering his entire family, but we find Hans- Jörg is the one character capable of real violence.

Agnes, whose title role affords her little screen time, is a cheerless male-to-female waif with AIDS or some other wasting disease, who may or may not have been molested by her father. Sometimes sheâs a go-go dancer, but mostly sheâs a full-time martyr capable of superhuman feats of passive-aggression. When Hans-Jörg bounds forth from his parallel universe of romantic comedy to tell his sister all the good news about his love life, Agnes just sits, with smile transfixed, and patiently bleeds all over her chair. And a description of that scene is really all you need to understand the filmâs entire tone: the truest moment of black comedy is unintentional, and Roehlerâs cynicism-clad nostalgia will be no match for his hardboiled audience.